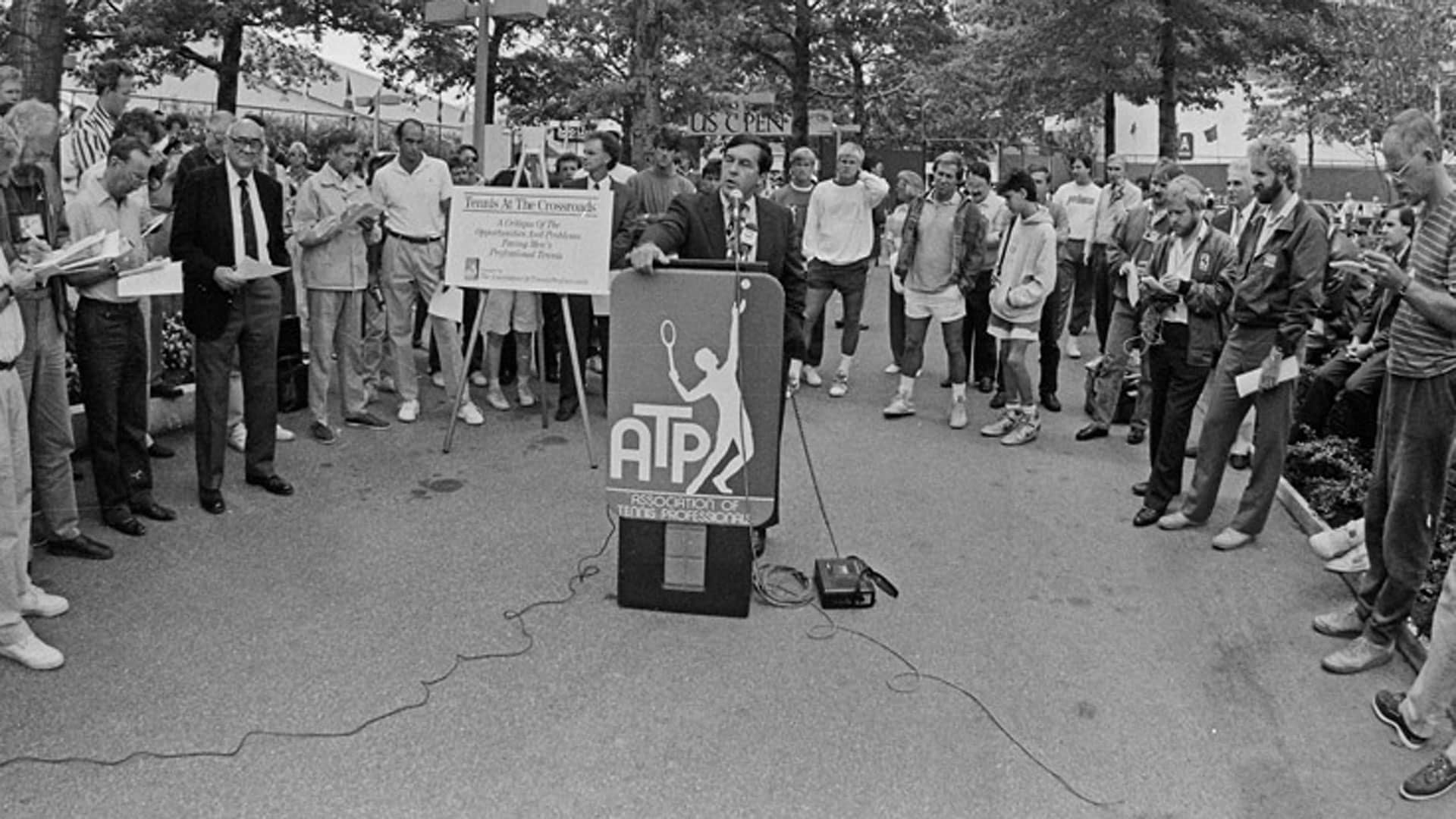

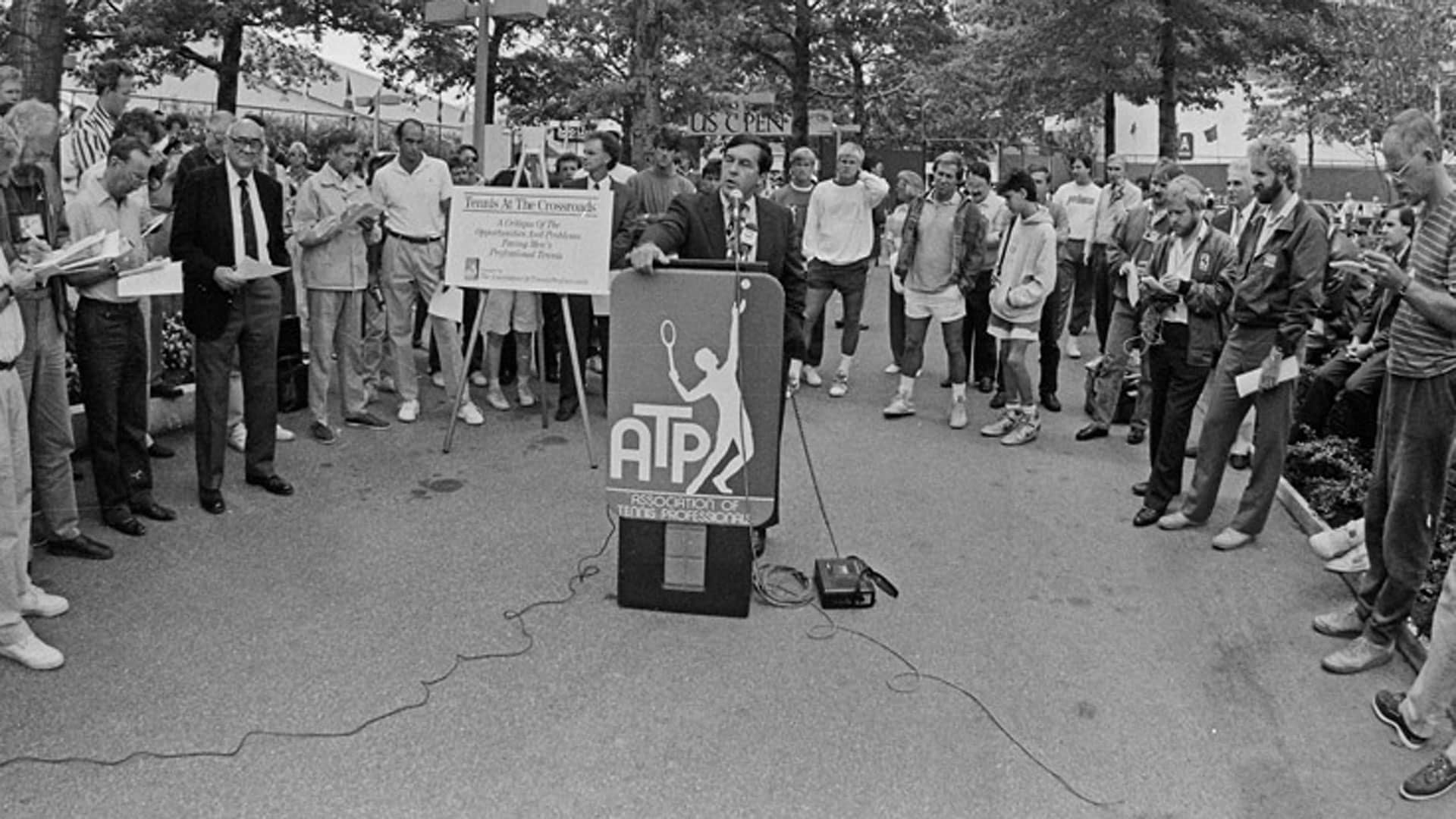

Few tennis media conferences have resonated like 'The Parking Lot Press Conference', held 25 years ago on 30 August 1988, a seminal moment in ATP history.

With the ATP logo hastily duct-taped to the podium, a rented PA system and a parking lot for a venue, the 1988 press conference that crystalised momentum for the birth of the ATP Tour could be called 'no frills' at best. But as ATP CEO Hamilton Jordan delivered ‘Tennis at the Crossroads’, a critique of the opportunities and problems facing men's professional tennis, the gathering outside the gates of the US Open had immediate - and lasting - impact.

Its roots were long-standing, but in the space of 16 months men’s professional tennis changed irrevocably due to the foresight of the ATP Board, the world’s leading players and the political nous of one man determined to make a positive change for a sport that had been in a state of flux.

When the ATP was created in 1972, founding fathers had debated the option of creating their own circuit. But, without the financial security and the confidence, it joined tournament directors and the International Tennis Federation (ITF) to form the Men's International Professional Tennis Council (MIPTC), which ran the men’s circuit from 1974 to 1989.

But by late 1986, players were unhappy. Drained by the number of tournaments on the calendar, unhappy with how the way tennis was being marketed and frustrated by regularly seeing its three Council representatives outvoted by a total of six ITF and tournament reps., the status quo was no longer acceptable.

Brian Gottfried, who was ATP President from 1986 to 1989, says, “The players were concerned that they didn’t have an equitable voice in the running of the sport and they were also looking for a way to better promote a game that we felt was being under promoted.” It was time to take control.

Enter Jordan, a one-time White House Chief of Staff to the President of the United States Jimmy Carter. In February 1987 he joined the ATP as its chief executive officer, following an unsuccessful 12-month campaign in the state of Georgia to gain a seat in the U.S. Senate. “Ray Moore and Harold Solomon were responsible for choosing Hamilton Jordan out of left field as ATP CEO,” recalls former ATP European Director Richard Evans. “It was a startling choice, but it certainly got the job done.”

Says Solomon, “Even though there were many qualified people Hamilton blew us all away with his presentation. He had obviously done his homework and had taken a month to visit and interview many of the prominent people in the tennis industry. He spoke to agents, television executives, the ITF, the Slams, tournament directors, and players and he gave us a story board presentation of the steps he would take and a time line for getting his vision accomplished. We figured that if he could figure out a way to deal with the Middle East politics then he would be able to handle the tennis world.”

Hamilton was joined by his aide, Brad Harris, who had previously assisted in a U.S. Presidential campaign and helped Jordan in 1986. “The ATP and its top players realised that the way the sport was run needed to change,” said Harris. “The conditions were not favourable at the time. Players were not being marketed right to grow the game. The basis for everything that happened was Hamilton’s recruitment.”

Jordan came on board at the age of 42 and within the year he had moved ATP headquarters from Dallas, Texas, to Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida. He also had a grand vision.

Rather than campaigning for Carter and politicians, Jordan immediately went to work by convincing tennis players that if they broke away from the MTC, the ATP would create its own circuit – a tour that respected the 12 weeks of major championship and Davis Cup play and ensured that they could have more money, work and power.

“He saw it as a political campaign rather than an administrative role,” said Harris. “Shortly after he took the role, he spoke to the top players, former players, Ray Moore and Charlie Pasarell, who although tournament directors at the time, had great experience. Hamilton felt that tennis was not the major sport it should be. He felt it should be run like the PGA Tour [golf], and he felt that the players should break away and start their own tour. He ran it like a political campaign. Building constituencies, getting them excited with his vision. It definitely had a campaign atmosphere.”

Once Jordan joined, he used the International Tennis Weekly to set out his goals and attacked the tennis establishment. “He had a disdain for eliticism,“ remembers Harris. “He thought the sport’s leaders considered themselves royalty and that made Hamilton, an outsider to tennis, a pretty attractive foil.”

Clear-the-air meetings at Wimbledon with Grand Slam officials in June 1988 did not go well. Two days prior to the start of the 1988 US Open, the ATP threatened to pull away from the MTC, the then governing body of men’s tennis, and start its own tour unless the council was restructured to give the players more control. Forty-eight hours later, on the first day of the championships, the ITF rejected the players' plan.

But, in the final paragraph of its five-page news release, the ITF offered a way to broker a deal. "If the present structure of the MTC is no longer acceptable to ATP's management, then the undersigned representatives of Wimbledon, the US Open, the French Championships [Roland Garros] and the Australian Open will ask the ITF, the governing body of tennis for the past 75 years, to form a new structure to carry on the worldwide work for the game."

By that stage though, Mats Wilander, Wimbledon champion Stefan Edberg and six other Top 10 players had already met to voice their support of the ATP’s vision. Bob Green, who was Director of Player Relations at the time, recalls, “We had signed commitments from eight of the Top 10 [no Jimmy Connors or Ivan Lendl] and I think 16 of the Top 20 at the time of the press conference.” Harris remembers fondly, “We got them to sign an agreement, but the funny thing was nobody had a pen. So they all had to sign the agreement in pencil.”

Confident that players weren't going to reach for an eraser, Jordan, Gottfried and other ATP officials continued to push.

Jordan wanted to hold a press conference on site during the US Open to address the media, but a request to use the interview room was initially denied. So plans were made for what would become known as the now-famous ‘press conference in the parking lot’ on Tuesday, 30 August.

“I remember being approached that morning by the USTA, which had changed its mind and would allow us to have a room on site,” says Gottfried. “But Hamilton said ‘No, we’ll do it as planned’. He knew what would grab attention. He was the one to lead us in this movement. That was his genius. He was a great strategic leader who knew how to create excitement and attention, and he was such a great speaker. We were the props.”

Green, who as a player was the 1984 Rookie of the Year, remembers, “It was political craftiness by Hamilton. In the end we probably could have used the media room, but it was more effective and symbolic to hold it in the parking lot. It became a metaphor for how the players were treated at the time… We were on the outside looking in.”

“On the morning of the press conference. Hamilton and I held a meeting with IBM pitching a vision of the Tour for potential sponsorship,” reveals Harris. At noon, on Tuesday, 30 August 1988, he stood outside the main gates of the US Open, surrounded by Ricardo Acuna, Russell Barlow, Charlie Beckman, Dan Goldie, Tim Mayotte, Paul McNamee, soon-to-be World No. 1 Wilander and other players – to witness Jordan announce the ATP’s plan.

“The press conference was held near where the Flushing Meadows trains went out at the time,” says Harris. “It took 15 minutes to set up the podium. We rented a portable PA system, paid off nearby police officers not to give us any trouble and invited the media at the last minute.”

Green admits, “It was pretty bare bones. We found a podium and duct-taped the ATP logo to it.” Mayotte recalls, “The conference was ‘just-enough’ organised to make it feel real, but also have a sense of a rebellion, a sense of authenticity.”